Our History

For Westgarth it was a memorable, if ‘comfortless’, scene, but one with a greater meaning. He located the camp at the heart of what would later become the University of Melbourne, close to where its first major building, the Quadrangle, would be built. He claimed that this showed the dramatic change brought about by the University, the height of ‘civilisation’, as it brought ‘enlightenment’ to the ‘primitive colony’. He missed the irony that on this occasion it was the Wurundjeri people who provided the light and who obligingly pointed the hapless Westgarth down the hill towards his home.1

Westgarth’s story reveals some of the dichotomies of the University and its purpose. On the one hand, the University was an undeniable agent of colonisation and dispossession, and of the imposition of European ideals onto an Australian setting. On the other, it was a local institution, with practical requirements in a developing colony. These ambiguities were reflected in the architectural fabric of the Quadrangle and in the long process by which it developed and changed over 165 years.

The Quadrangle is a building that has been constantly reimagined, renovated and extended to follow the changing nature of the University. Far from its presentation as an unchanging stone edifice, harking back to the earliest British universities, it is a symbol of renewal within an evolving institution.

The original plans for the Quadrangle are now lost, and the designs were amended several times during construction. From indicative etchings commissioned by the architect, Francis Maloney White, the intention was to erect a stone building around a central courtyard, with a short tower in the southern wing. It was modelled after recently constructed buildings, including St David’s College in Lampeter, Wales, and the Belfast and Cork campuses of Queen’s College, Ireland.2

The building was situated on the east–west ridgeline of the campus, amid surrounding terraces in the middle of an open park, which was created by workers who dammed the creek to create an ornamental lake and dug meandering pathways through both native and exotic plantings.3

The building was designed in Tudor Gothic style, which simultaneously denoted tradition and a connection with the historic seats of learning from which the University recruited its professors, and signalled its secular modernity, particularly in its avoidance of ecclesiastical features.4

At the ceremony to lay the foundation stone, on 3 July 1854, the first Chancellor, Redmond Barry, and the Lieutenant-Governor, Sir Charles Hotham, stressed the same theme: the University’s importance in providing a public good and helping to civilise the colony, while also responding to the colony’s immediate needs.5

The East and West Wings were the first to be built, and these provided apartments for the four original professors and their families, teaching rooms on the ground floor of the East Wing and an office and boardroom for the registrar in the south-west corner.

The apartments were designed according to the particular needs of the professors, which varied considerably. William Edward Hearn, Professor of History and Political Economy, was married with six children, while William Parkinson Wilson, Professor of Mathematics, pure and mixed, was a bachelor. This bespoke plan created problems for Martin Howy Irving, appointed to replace the first Professor of Classics, Henry Rowe, who died shortly after arriving in Melbourne. Irving found his lodgings, sized for Rowe, impossibly cramped, with only two bedrooms for his nine children.6

The imposing North Wing was the next to be constructed. It provided two raking theatres for the sciences, in which the professors gave lectures and scientific demonstrations. A museum was installed on the first floor, and an 1875 extension to the building provided additional floor space for a library.

It was during the construction of the North Wing that the University became an assembly point for stonemasons from this site and others to march to Parliament House in Spring Street in 1856. The march heralded a famous victory for the eight-hour-day movement, the stonemasons winning concessions and helping to spur the development of the labour movement.7

By the time the North Wing was constructed, the University had already determined that it could not proceed with the South Wing or its tower, owing to funding shortfalls. The South Wing would remain unfinished, with only its foundations visible above ground level, hinting at what might yet be built above.8

The building came to be known, in the self-deprecating Melbourne style, as the three-sided quadrangle. Photographs of the building were invariably taken from the back, making use of the light that reflected off the lake and obscuring the unfinished sections. The open courtyard was planted with a central lawn pathway, which was bounded by gardens of flowers and shrubs on either side. Creepers were trained to grow over the walls of the southern face, giving the sandstone walls the appearance of being weathered and aged rather than unfinished.

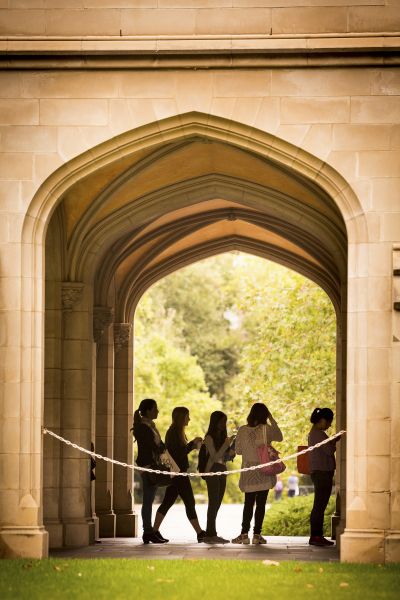

The Quadrangle was often referred to by shorthand as the ‘University’. It was the hub of teaching, the venue for major ceremonial events, such as the annual Commencement, and the forum where students met to discuss their work and the issues of the wider world.

The collegial atmosphere it fostered was enhanced by the decision to grant the new Melbourne University Union, established in 1884, the use of Wilson’s old apartment—which had more recently been inhabited by his successor, Edward Nanson. The Union brought together male staff, students and graduates, and its rooms offered respite from the chill southerly winds that blew into the open quadrangle. In 1886, the Princess Ida Club, for female staff, students and graduates, moved into Hearn’s former apartment, and the two societies, divided on gender lines, faced one another across the courtyard. By 1907, the Quadrangle held more than 500 student lockers, enough for most of the University’s students.9

This was the stomping ground of generations of students. The fondness for the Quadrangle was reflected in poems such as ‘Leaving the Shop’, published in 1899 in the University magazine Alma Mater:

- Tread with me the old quadrangle

Where our course was set.

All was once a seeming tangle,

Is it tangled yet?10

The Quadrangle was, in its pomp, a lively scene, the building’s gnarled corners embodying the formative processes of a university education.

Yet the Quadrangle’s place in the wider University was already changing. As the University expanded in both its size and its range of activities, it built new buildings separate from the still unfinished Quadrangle.

Some of these new buildings, such as those for medicine in the north-east corner of the campus and the engineering building on the southern boundary, were deliberately separated in order to ensure adequate distance from the noises and smells they contained. Others, including a natural history museum and a biology building, were built around the lake. The Union and Princess Ida Club outgrew their Quadrangle lodgings and moved into the natural history museum in 1911.

All the while, the University declined opportunities to enclose the fourth side of the Quadrangle. The gift of the pastoralist Samuel Wilson for a ceremonial hall presented such a chance, but instead of Wilson Hall forming the southern wing, it was constructed separately, in 1882, to the south-east of the Quadrangle’s jagged southern walls. A second hall to house a library, envisaged to be built on the opposite corner to restore the symmetry of the southern aspect, never eventuated.11

The prospect of completing the Quadrangle was again raised in the planning for the Old Arts building, which opened in 1924. However, the University again favoured a separate construction, even though its clock-tower was inspired by the original plans for the Quadrangle.12

The construction of the Old Arts building did, however, prompt the redevelopment of the Quadrangle. Its large lecture theatres relieved the Quadrangle’s old raking theatres in the North Wing of their teaching burden. By this point, these had become hopelessly dilapidated—in the opinion of one professor, even endangering the health of those attending lectures there—and they were demolished in 1925.13 The North Wing subsequently housed the University library.

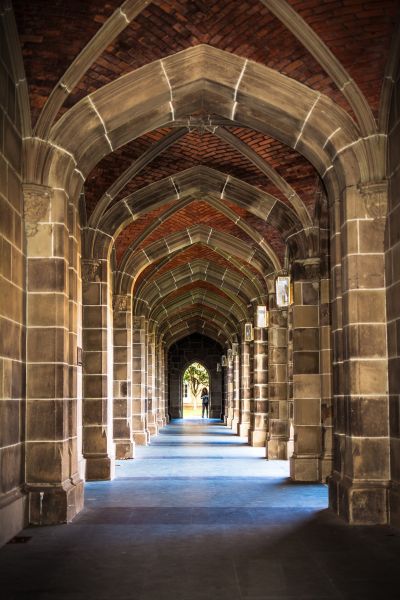

The unfinished East and West Wings were also capped by southern extensions that provided a more polished southern aspect, and the vaulted arcade erected along the North Wing was extended down the east and west flanks. Meanwhile, the former apartments, which had since been vacated, were renovated. Redundant staircases were removed, halls opened and domestic rooms converted into offices.

The Quadrangle continued to provide teaching facilities for several faculties, including Arts, Commerce and Law, but, gradually, the Law Faculty grew to assume ownership of the building. The transfer of the general library collection to the new Baillieu Library building in 1959 allowed the North Wing to become a specialist law library, and the old library space was extended to accommodate a bookroom and a bank.

Although administrators and staff from the Law Faculty made repeated calls to be moved into a new larger building after the Second World War, the building itself was held in fond regard by many as a fitting complement to the study of law, echoing the majesty of the law courts and some of the old law chambers.14 More space was made in 1969 through the erection of new lecture rooms between the Quadrangle and Old Arts and the opening of the Raymond Priestley Building in 1970, which relieved the Quadrangle of administrative staff.

It was also in 1969 that the Quadrangle was finally enclosed, 115 years after building commenced. The new wing, designed by Rae Featherstone in sympathetic style and retaining all of the existing building, but also encroaching into the courtyard, contained a new council chamber. With the construction of the South Lawn and Underground Car Park in 1972, the southern vista was again redefined.

The undercroft beneath the South Wing was only completed in 1981, creating a whole new space on the campus. Often mistaken for one of the oldest parts of the University, this new space, with its extensive vaulted arcade, has since become a favourite location for wedding and graduation photographers.

After the Law Faculty vacated what to many had become the ‘Law Quadrangle’ in 2002, the building housed various parts of the University, including Classics and Archaeology. As had occurred a century earlier, its interiors degraded while different proposals for its redevelopment were discussed. It is fitting, then, today, that a new purpose for the building has been found as part of the project to restore the University’s centre, to revive the old Commencement and to gather staff, students, graduates and the public once more at the heart of the University campus.

1 William Westgarth, Colony of Victoria: Its History, Commerce, and Gold Mining; Its Social and Political Institutions; Down to the End of 1863. With Remarks, Incidental and Comparative, Upon the Other Australian Colonies (London: Sampson Low, Son, and Martson, 1964), 445–6.

2 George Tibbits, The Quadrangle: The First Building at the University of Melbourne (The University of Melbourne: The History of the University Unit, 2005), 15–16.

3 Geoffrey Blainey, A Centenary History of the University of Melbourne (Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press, 1957), 16.

4 R.J.W. Selleck, The Shop: The University of Melbourne, 1850–1939 (Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press, 2003), 7.

5 ‘The University and the Public Library’, The Argus, 4 July 1854, 4–5.

6 Tibbits, The Quadrangle, 44–56.

7 Julie Kimber and Peter Love, ‘The Time of Their Lives’, in The Time of Their Lives: The Eight Hour Day and Working Life, ed. Julie Kimber and Peter Love (Melbourne: Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, 2007), 1–14.

8 Ernest Scott, A History of the University of Melbourne (Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press, 1936), 18–19.

9 Tibbits, The Quadrangle, 115.

10 ‘Leaving the Shop (to H.S.L.)’, Alma Mater 4, no. 2 (1899).

11 Tibbits, The Quadrangle, 106.

12 George Tibbits, The Old Arts Building, University of Melbourne: History and Conservation Guidelines (Parkville, Vic.: The University of Melbourne, 1995).

13 T.G. Tucker to Chancellor, 28 January 1919, 1919/350a, 1999.0014, University of Melbourne Archives.

14 John Waugh, First Principles: The Melbourne Law School, 1857–2007 (Carlton, Vic.: Miegunyah Press, 2007), 271–2.